Most investors instinctively answer this question with an emphatic “Yes.”

After all, a low price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio suggests that a stock is “cheap” compared to its profits — and history shows that, over long periods, low-P/E portfolios often outperform high-P/E ones.

But is every low-P/E stock a hidden gem? Not necessarily.

While the P/E ratio is a powerful valuation shortcut, it can mislead when used in isolation. Let’s break down what it really tells us — and where it can go wrong.

Understanding the Market’s Rule of Thumb

Type of Stock | Market View | Interpretation |

High P/E | Reflects optimism and expectations of strong future earnings | May be expensive or overvalued |

Low P/E | Reflects pessimism or weak outlook | May be undervalued or cheap |

This simple logic works sometimes — but not always.

To see why, consider the case of PC Jeweller Ltd.

Case Study: PC Jeweller Ltd.

Year | P/E Ratio |

2016 | 16 |

2017 | 23 |

2018 | 8.6 |

2019 | 2.2 |

2020 | NA |

At first glance, a P/E of 8.6 or 2.2 might look like a bargain.

But this “cheap” valuation came after the company performed badly leading to a sell off.

Between FY18 and FY20, profits collapsed — the company even reported operating losses in March 2019.

An investor chasing the low P/E would have faced steep losses.

The lesson: a low P/E can reflect distress, not opportunity.

Why Stocks Trade at Low P/Es

1. Earnings Fluctuations

Profits can spike temporarily from one-off events — like asset sales or commodity price jumps — that distort the P/E ratio.

For example, graphite-rod makers looked cheap in 2018 when rod prices soared. When prices normalized, earnings fell and valuations corrected.

Likewise, companies with high receivables or negative cash flows (e.g., Va Tech Wabag) may appear inexpensive but signal poor earnings quality.

2. Low-Growth Businesses

Companies with limited future growth — say, mature textile or paper manufacturers — deserve low valuations.

A business that can’t reinvest profitably won’t justify a high multiple, no matter how solid its current profits.

3. Cyclical Industries

Cyclical sectors like cement, metals, or mining swing between boom and bust.

During peaks, profits surge, and the P/E looks deceptively low.

During downturns, earnings shrink, and the same stock looks expensive.

That’s why analyzing sector cycles and median P/E trends is essential.

4. Industry Norms

Each industry carries its own “typical” valuation range.

For instance:

Consumer staples (FMCG) command high P/Es due to steady growth and high returns on capital.

Steel and power utilities historically trade at low P/Es (6–14 ×) because their earnings are cyclical and capital-intensive.

Thus, Tata Steel trading at 8 × earnings isn’t necessarily “cheap” — it’s normal for its sector.

5. Corporate-Governance Risks

Companies with a history of mistreating minority shareholders or poor disclosure trade at a discount to fair value.

Even if profits look good, markets assign lower multiples due to the risk of repetition.

How to Analyse Low P/E Stocks the Right Way

1. Compare Against Industry Median P/E

Different industries deserve different valuations.

Always compare a stock’s multiple with its industry median, not the average (which can be distorted by outliers).

For example:

An FMCG stock at 20 × P/E may be cheaper than a power stock at 15 ×, because FMCG firms grow faster with minimal reinvestment.

Conversely, if FMCG trades at 35 ×, and power at 7 ×, the power company might offer better value.

2. Determine a Rational P/E Based on Growth

Estimate a fair or rational P/E by projecting earnings growth, longevity, and stability.

Factors like inflation and interest rates also matter.

A practical way to do this is the discounted P/E model, which forecasts 10-year growth, assigns a P/E a later date EPS, and discounts it back to today’s value. MoneyWorks4Me applies this framework to calculate a stock’s MRP (fair value).

3. Use Alternative Valuation Multiples

When earnings fluctuate, other ratios offer clarity:

Price-to-Sales (P/S)

EV/EBITDA (Enterprise Value to Operating Profit)

Price-to-Book (P/B)

Comparing these across 10-year averages gives a truer sense of valuation consistency.

MoneyWorks4Me provides all these metrics historically to simplify comparison.

4. Use “Normal-Year” EPS Instead of Trailing EPS

Cyclical or event-hit businesses (e.g., airlines post-pandemic or hotels post-terror attacks) can show distorted or negative EPS.

In such cases, use steady-state or normalized earnings to calculate P/E.

This avoids undervaluing strong businesses temporarily facing weak profits.

Key Takeaways

Myth | Reality |

Every low P/E stock is undervalued | Some are cheap for good reasons — poor earnings, weak governance, or low growth |

High P/E always means overvalued | Quality companies with strong ROCE and durability deserve premium valuations |

P/E is the only metric that matters | Use it with other valuation and quality indicators for a complete picture |

The Bottom Line

Low P/E stocks can offer opportunity — but only when backed by quality, growth, and strong financials.

Blindly chasing low-P/E “bargains” can lead to painful value traps.

Evaluate the business first, not the multiple.

Because in the long run, earnings power drives value, not cheap optics.

Already have an account? Log in

Want complete access

to this story?

Register Now For Free!

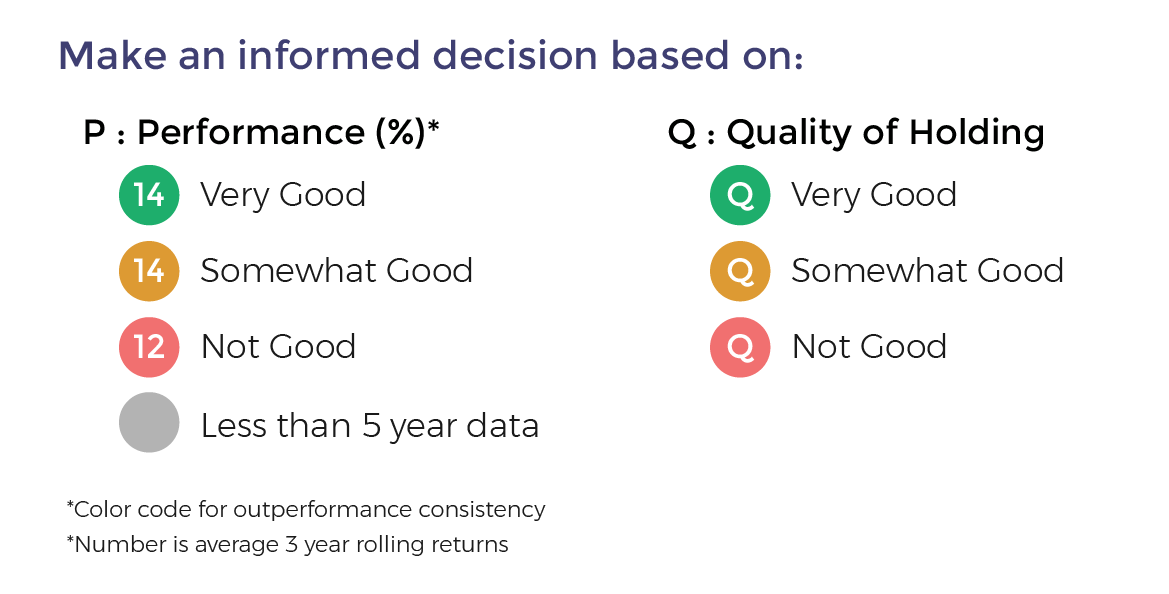

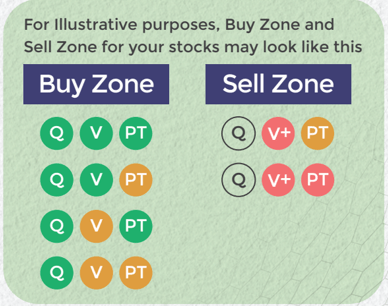

Also get more expert insights, QVPT ratings of 3500+ stocks, Stocks

Screener and much more on Registering.

Comment Your Thoughts: